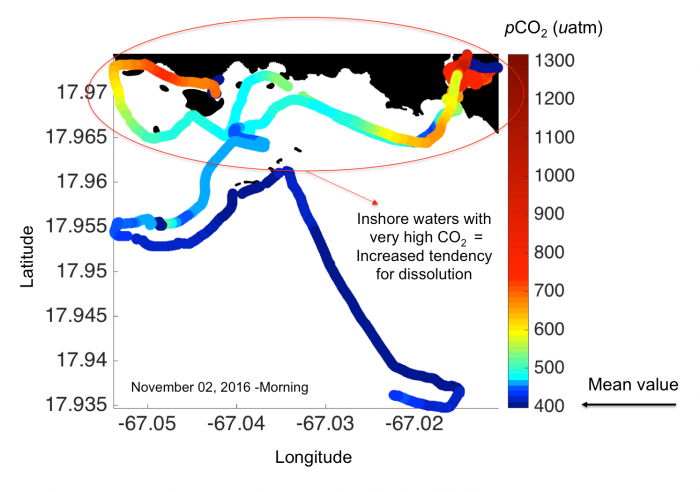

Coral reefs act as coastal barriers against incoming wave energy which would otherwise cause inundation and erosion. Their skeleton is made out of calcium, similar to our bones. When exposed to slightly more acidic water, resulting from an increased level of atmospheric CO2, they can undergo dissolution and weakening. The potential consequences could be devastating as a debilitated skeleton would not be able to withstand energetic storm driven waves. To this end, CARICOOS, Sea Grant, UPRM and UNH have embarked on a study to assess the potential vulnerability of natural coastal barriers in La Parguera, PR to ocean acidification. This two-year project consists of a series of field campaigns aiming at characterizing carbonate chemistry around key locations in La Parguera coral reef-seagrass-mangrove ecosystems. A state-of-the-art flow-through system developed and tested at UNH was installed aboard the M/V Trópico in order to map in real time the chemical parameters of the area. Several current meters and Lagrangian drifters were also deployed to investigate the dominant current patterns and hydrodynamic time scales. Preliminary findings show inshore waters exhibiting pCO2 levels that can be up to three times higher than those less than three miles offshore, suggesting than nearshore barriers can be particularly vulnerable to dissolution. Moreover, in the vicinity of a mangrove system water acidity can vary twofold within eight hours due to temperature changes and nighttime respiration in the absence of photosynthesis. These unprecedented observations may support the hypothesis that the organic carbon produced by mangroves and seagrasses is a driver for high respiration rates and nighttime pCO2 in nearshore areas.

- Spatial distribution of CO2 levels at La Parguera Marine Reserve.

- Flow-through system onboard of M/V Trópico (photo credit: Chris Hunt).

- M/V Trópico as it transects around La Parguera (photo credit: Pichón Duarte).

- Melissa Meléndez packs the equipment as the three-day long field campaign comes to an end.

- MAPCO2 buoy at La Parguera Marine Reserve. This CARICOOS asset has been collecting data of carbonate chemistry near Cayo Enrique since 2009 (photo credit: Pichón Duarte).

This project is sponsored by the Puerto Rico Sea Grant College Program and CARICOOS. Its Principal Investigator is Joe Salisbury (UNH). Other scientists include Melissa Melendez (UNH), Julio Morell (CARICOOS & UPRM), and Sylvia Rodríguez-Abudo (CARICOOS and UPRM).